Noise Complaints

One of the main ways that noise issues are dealt with, in Mexico City and elsewhere, is through noise complaint processes. The source of a sound often determines what agency, if any, will accept complaints about a sound. For example, in Mexico City, noise from commercial activities, construction, or industry is handled by different agencies than noise in residential spaces.

Noise complaints are a reactive way of addressing noise issues—meaning they happen after the fact. For a few reasons, they also cannot provide a complete picture of noise issues in a city. First, it’s not possible to complain about all types of noise issues through complaint channels in a given city. Additionally, some residents may be more comfortable using government complaint mechanisms than others. Noise complaints may also cluster in more affluent areas of a city, or in areas where contested new development is taking place and there are disagreements about how to use a neighborhood’s spaces. Complaints can also be used to work out other conflicts and create administrative trouble for a person’s neighbors.

That said, noise complaint data can provide information about where some noise conflicts are occurring and what types of sound are being cited. Studying complaint records also illustrates how complaints are investigated and concluded and explores interaction points between residents and city government. In my research, I found that the process of complaining, which frames noise and other environmental issues as individual grievances, simultaneously positions noise as an individual problem, for individual residents to deal with, and creates a significant amount of work for staff as they sort through real and potentially bad faith noise complaints.

The Attorney General for Environmental and Territorial Issues in Mexico City (PAOT) receives and investigates complaints about a variety of issues, including noise from commercial, industrial, and construction sources. Since they were founded in 2002, the agency has received over 10,000 noise complaints. The PAOT is not the only city entity that is technically responsible for handling sound issues but it is the entry point for many noise problems and maintains the best publicly available data on noise complaints they receive.

In my project, I conducted an analysis of the PAOT’s publicly available noise complaints data to understand:

whether investigators were able to perceive sound during an inspection,

whether a noise measurement found a noise violation,

how a complaint was resolved,

what type of business was cited,

and in some cases, what type of sound was being complained about (e.g., live music, mechanical equipment, etc.).

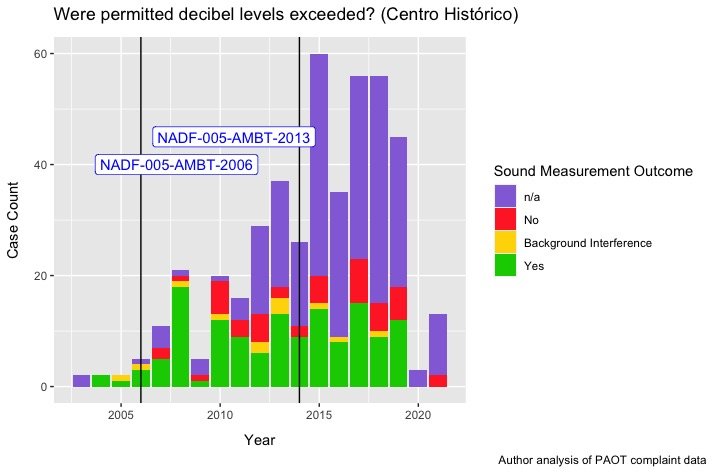

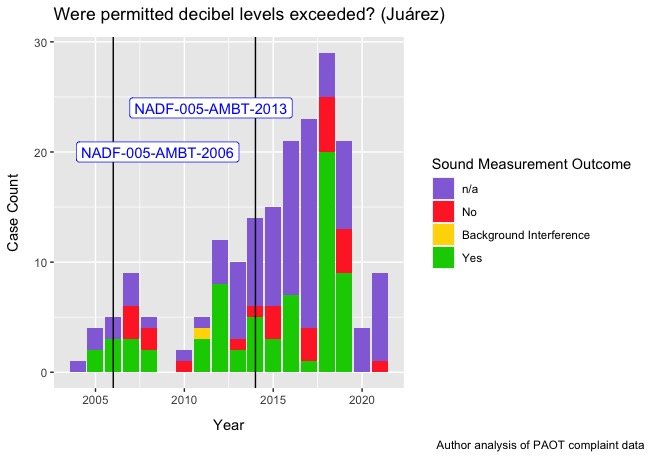

To do this, I used PAOT records and PDF files of complaint resolutions to create a dataset of complaints for the two neighborhoods where I conducted ethnographic research (colonia Juárez and the Centro Histórico). Between January 2002 and December 2021, those areas received 737 complaints total, accounting for approximately 7% of all noise complaints the PAOT had received by the end of 2021. You can read more about my technical process and analysis on this page.

Noise Complaint Analysis

When looking at all noise complaints, the average length of time between when the PAOT receives a complaint and when it is concluded has decreased since 2010. However, that period of time is still lengthy, with an average of 144 days across all districts in 2019 (the last year where processing times were unaffected by the pandemic). This is well within the window permitted by law, but it means that in urgent cases, someone might have to live with a noise problem for an extended period of time before an authority can intervene.

The specific sound source wasn’t mentioned in every noise complaint, but complaint documentation regularly noted the type of sound cited. This information gives a picture of the types of sounds that are common, or commonly complained about, in a given neighborhood.

In 66% of the cases I reviewed across Juárez and the Centro, investigators were able to perceive some kind of sound. However, in cases where that didn’t happen, that didn’t mean there was never any sound present. In some cases, it might mean that the sound was part of a one-off event, or was no longer present because of a delay between when a complaint was filed and when investigators were able to visit.

When investigators did perceive sound, cases might go a few different ways. Especially when a business or operator wasn’t interested in finding a compromise, investigators might need to take a decibel level reading with a sound level meter. When investigators did conduct sound level meter readings, they often found decibels levels over permitted limits. However, in some cases, background noise made it difficult to say if the sound source cited in a complaint was violating permitted decibel levels. In a space that’s already loud, it can be difficult to distinguish one sound from another.

Cases were concluded for a variety of reasons: sometimes a business would cease to operate, and sometimes they would be closed by another agency for a related or totally different reason. In many cases, even including some cases where investigators found sound over permitted decibel levels, the PAOT was able to get an operator to voluntarily agree to modify their noise practices. However, there is no formal follow-up practice to verify that businesses continue to comply long-term. That type of information is conveyed in the negative through new complaints.